Introduction: Bridal Gifts, Dowry, and Mehr Rights in Pakistan – A Guide

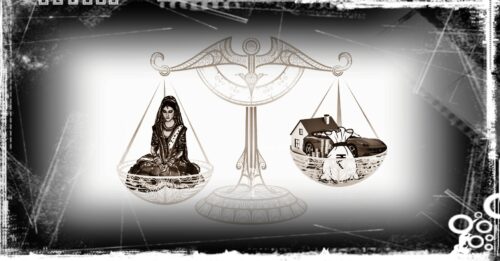

In Pakistan, the rights of women to bridal gifts, dowry, and Mehr (dower) are deeply rooted in both Islamic principles and national laws. However, cultural practices and a lack of awareness often overshadow these legal protections, leaving many women unaware of their entitlements. Bridal gifts, which include jewelry, cash, and property, are often misunderstood as shared assets between spouses, while dowry and Mehr are frequently misrepresented or undervalued. This guide aims to clarify the legal and religious frameworks that safeguard women’s rights to these assets, ensuring they are empowered to claim what is rightfully theirs.

Islamic law, as enshrined in the Quran, explicitly grants women the right to own and manage their property independently. Pakistani law further reinforces these rights through legislation such as the Married Women’s Property Act (1874), the Muslim Family Laws Ordinance (1961), and the Prevention of Anti-Women Practices Act (2011). Despite these protections, societal norms and regressive traditions often prevent women from exercising their rights fully. This guide will explore the legal status of bridal gifts, dowry, and Mehr, along with practical steps women can take to secure their property rights.

By understanding the legal and religious foundations of these rights, women can better navigate the challenges posed by cultural practices. Whether it’s claiming ownership of bridal gifts, asserting rights to Mehr, or addressing inheritance disputes, this guide provides a comprehensive overview to help women protect their assets and uphold their dignity. Let’s delve into the specifics of these rights and how they can be enforced in Pakistan.

Women’s Property Rights in Pakistan: Bridal Gifts, Dowry, and Mehr in pakistan

In Pakistan, women’s property rights are enshrined in constitutional guarantees, Islamic law, and progressive legislation. Yet, deeply rooted patriarchal norms, weak enforcement, and socioeconomic disparities systematically deny women control over land, inheritance, and marital assets. This gap between legal frameworks and lived realities perpetuates gender inequality, leaving millions of women economically vulnerable. Here’s an in-depth analysis of the legal landscape, cultural barriers, and pathways to reform.

1. Constitutional and Islamic Foundations

Pakistan’s Constitution (Article 23–24) guarantees equal rights to acquire, own, and dispose of property. Islamic law further reinforces these rights:

- Quranic Inheritance Rules: Women are entitled to fixed shares (e.g., daughters receive half of a son’s portion).

- Mehr (Dower): A mandatory payment from the groom to the bride, legally recognized as her exclusive asset under the Muslim Family Laws Ordinance (1961).

- Stridhan: Bridal gifts (e.g., jewelry, cash) remain the wife’s absolute property.

Despite these protections, 67% of Pakistani women do not own land or property (World Bank, 2023), reflecting systemic disenfranchisement.

2. Inheritance Rights: The Battle for Land

Under Islamic law and the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act (1962), women’s inheritance shares are non-negotiable. However:

- Cultural Barriers: Families pressure women to sign away their shares (tanazul) through coercion or emotional blackmail. In rural Sindh, 80% of women forfeit inheritance to maintain “family harmony” (UN Women, 2022).

- Fraudulent Practices: Male heirs collude with revenue officials to exclude women’s names from land records (fard).

- Legal Loopholes: Weak documentation and tribal justice systems (jirgas) override statutory laws.

Case Study: In 2023, the Supreme Court ruled in Saima Bibi v. State that verbal waivers of inheritance are invalid if coerced, mandating criminal penalties for disinheritance.

Bridal Gifts Ownership in Pakistan Legal Rights and Cultural Complexities

In Pakistan, bridal gifts (jahez or dahej)—ranging from jewelry and clothing to household items—are traditionally given to the bride by her family or the groom’s family as a gesture of goodwill and financial support. However, ownership of these gifts is often mired in ambiguity due to overlapping cultural norms, societal expectations, and legal frameworks. While Islamic law and Pakistani civil statutes explicitly recognize bridal gifts as the bride’s exclusive property, real-world practices frequently undermine this right. Families may pressure brides to “share” gifts with in-laws or return them during marital disputes, reflecting a gap between legal entitlements and patriarchal customs.

Legally, bridal gifts fall under the concept of stridhan (a woman’s absolute property) in South Asian jurisprudence. Pakistan’s West Pakistan Muslim Personal Law (1962) and judicial precedents (e.g., 2021 Lahore High Court rulings) reinforce that these assets cannot be claimed by the husband, his family, or even the bride’s parents after marriage. Despite this, weak documentation (e.g., unrecorded verbal promises) and lack of awareness leave many women unable to assert ownership. For instance, gold jewelry—often a bride’s most valuable asset—is sometimes seized by in-laws under the guise of “safekeeping,” effectively disempowering the bride.

The issue is further complicated by regional disparities. In urban, educated households, brides may retain control over gifts, while rural areas see higher rates of coercion, especially in low-income families where gifts are viewed as “compensation” to the groom’s family. Legal reforms like the Protection of Women’s Property Rights Act (2020) aim to criminalize the forced seizure of bridal gifts, but enforcement remains inconsistent. To safeguard rights, experts advise brides to:

- Document all gifts in writing (e.g., marriage contracts, gift deeds).

- Store high-value items (e.g., gold) in secure, independent spaces (e.g., bank lockers).

- Seek legal aid through organizations like Pakistan’s National Commission on the Status of Women if ownership is disputed.

This tension between tradition and law underscores a broader struggle for women’s autonomy in Pakistan—one where bridal gifts symbolize not just material wealth, but agency and dignity. https://wallstreet.pk/category/blogs/

Dowry Laws in Pakistan

In Pakistan, dowry (jahez)—the practice of transferring cash, goods, or property from the bride’s family to the groom’s family as a precondition for marriage—is a deeply entrenched social custom, despite being legally prohibited since 1976. Rooted in patriarchal traditions, dowry perpetuates gender inequality, financial exploitation, and domestic violence. To combat this, Pakistan has enacted laws like the Dowry and Bridal Gifts (Restriction) Act, 1976, and the Prevention of Anti-Women Practices (Criminal Law Amendment) Act, 2011. These laws criminalize demanding, giving, or receiving dowry, imposing penalties of up to 5 years imprisonment and fines.

However, enforcement remains inconsistent. The 1976 Act limits dowry items to “necessities” (e.g., clothing, basic furniture) and caps their value at PKR 5,000—a figure unchanged since its enactment, rendering it irrelevant in modern times. The 2011 Act goes further, penalizing coercive dowry demands (Section 4), but cases are rarely reported due to social stigma, fear of family dishonor, and women’s economic dependence. A 2020 UN Women report found that 84% of Pakistani marriages still involve dowry, with rural areas seeing higher rates of exploitation.

The law also distinguishes between dowry (gifts to the groom’s family) and bridal gifts (assets owned exclusively by the bride). While dowry is illegal, bridal gifts are protected under property rights laws. Yet, families often blur this line, pressuring brides to “donate” their gifts to in-laws. Judicial precedents, such as the 2022 Islamabad High Court ruling, have reaffirmed that dowry-related harassment (e.g., demands for additional payments post-marriage) is punishable, but legal literacy gaps and corrupt policing dilute accountability.

Cultural norms further undermine these laws. Dowry is often framed as a “voluntary gift,” masking coercion, and low conviction rates (less than 2% of reported cases) deter victims from seeking justice. Recent amendments, like the 2022 Anti-Rape (Investigation and Trial) Act, indirectly strengthen dowry-related protections by prioritizing women’s testimonies, but systemic reform requires grassroots education, stricter enforcement, and redefining marital expectations.

Mehr (Dower) Rights in Pakistan: Islamic Mandates and Modern Realities

Mehr (or dower) is a fundamental Islamic right granted to brides, serving as a financial safeguard and symbol of respect within marriage. Under Islamic law and Pakistan’s Muslim Family Laws Ordinance (1961), Mehr is a mandatory payment or asset pledged by the groom to the bride, which becomes her exclusive property. Unlike dowry (jahez), which flows from the bride’s family to the groom’s, Mehr is designed to empower women, ensuring economic security in case of divorce or widowhood.

Legal Framework and Types of Mehr

Mehr can be classified into two categories:

- Prompt Mehr (Mu’ajjal): Paid immediately after marriage, often in cash, gold, or property.

- Deferred Mehr (Mu’wajjal): Paid upon divorce, widowhood, or a predefined trigger event.

The amount is mutually agreed upon before the marriage contract (Nikah). While Islamic principles emphasize fairness, cultural practices often pressure women to accept nominal sums (e.g., PKR 1,000) to avoid appearing “greedy.” However, courts have upheld brides’ rights to claim realistic Mehr amounts. For instance, a 2023 Lahore High Court ruling mandated a husband to pay PKR 5 million in deferred Mehr after divorce, reinforcing its legal enforceability.

Challenges in Enforcement

Despite its protective intent, Mehr rights face systemic hurdles:

- Social Stigma: Families may discourage brides from demanding fair Mehr to maintain “good relations” with in-laws.

- Documentation Gaps: Verbal agreements or vague Nikah contracts (e.g., “as per Sharia”) lead to disputes.

- Economic Coercion: Women in low-income households often waive Mehr under pressure or lack resources to pursue legal claims.

A 2021 study by the Aurat Foundation revealed that 62% of divorced women never received their deferred Mehr, citing fear of retaliation or lack of legal aid.

Strengthening Mehr Rights

Recent reforms aim to bridge these gaps:

- Digital Nikah Namas: Punjab and Sindh now mandate detailed, standardized marriage contracts specifying Mehr type, amount, and payment terms.

- Judicial Activism: Courts increasingly treat non-payment of Mehr as a breach of contract, enforceable under the Contract Act (1872).

- Awareness Campaigns: NGOs like Shirkat Gah educate women on negotiating and documenting Mehr.

For brides, experts recommend:

- Negotiate a realistic Mehr reflecting inflation and future security.

- Document details in the Nikah Nama (e.g., payment deadlines, assets).

- Assert rights proactively: File claims under Section 9 of the Family Courts Act (1964) if Mehr is withheld.

Mehr remains a cornerstone of women’s financial autonomy in Pakistan—a right that, when enforced, can counterbalance systemic gender disparities.

Sharia Law and Women’s Property Rights in Pakistan: Principles vs. Practice

In Pakistan, Sharia law forms the bedrock of women’s property rights, derived from the Quran, Hadith, and centuries of Islamic jurisprudence. Islam explicitly grants women the right to own, inherit, and manage property—a revolutionary concept in 7th-century Arabia that remains legally binding in Pakistan today. However, patriarchal interpretations, cultural distortions, and weak enforcement often dilute these rights, creating a stark divide between religious ideals and lived realities.

Sharia’s Progressive Framework

Under Islamic law, women’s property rights are unambiguously defined:

- Inheritance: The Quran (Surah An-Nisa) mandates fixed shares for female heirs. Daughters receive half the share of sons, widows inherit 1/8 of the estate (if children exist), and mothers are entitled to 1/6. These shares are compulsory and cannot be revoked by male relatives.

- Ownership: Women have absolute control over their assets, including income, gifts (e.g., bridal gifts/Mehr), and inherited property. They can buy, sell, or lease property without spousal or familial consent.

- Marital Property: Sharia prohibits husbands from claiming ownership of their wives’ assets, even if the wife earns more.

For example, if a father dies leaving a son and daughter, the daughter is entitled to 1/3 of the estate, while the son receives 2/3—a ratio critics argue is unequal but scholars defend as balanced by men’s financial obligations (e.g., providing Mehr, supporting families).

Cultural Contradictions and Violations

Despite these clear directives, practices in Pakistan frequently violate Sharia principles:

- Disinheritance of Daughters: Families pressure women to relinquish inheritance through written or verbal waivers (often under threat of estrangement). In rural Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 67% of women forfeit their shares, per a 2020 UN Women report.

- Fraudulent Transfers: Male relatives exploit land registry loopholes to transfer titles illegally.

- Misuse of “Wasiyat” (Will): While Sunni Islamic law limits wills to 1/3 of the estate, families use this to further reduce women’s shares.

A 2021 Supreme Court case (Saima Bibi v. Muhammad Aslam) highlighted this conflict. The court ruled that a daughter’s inheritance right is “non-negotiable” under Sharia, even if she signed a waiver, as coercion invalidates such agreements.

Legal and Grassroots Challenges

Pakistan’s legal system theoretically upholds Sharia through:

- The Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act (1962): Enforces Islamic inheritance rules, overriding customary laws like watta satta (land swaps).

- Section 4 of the Muslim Family Laws Ordinance (1961): Criminalizes disinheriting women.

- Corrupt Land Revenue Departments: Officials collude with male heirs to tamper with records.

- Lack of Legal Awareness: Only 18% of women in Pakistan know their inheritance rights (Aurat Foundation, 2022).

- Parallel Justice Systems: Tribal jirgas and panchayats often prioritize patriarchal customs over Sharia.

Pathways to Reform

- Judicial Accountability: Specialized family courts and mobile justice units (e.g., Punjab’s Women-on-Wheels initiative) can expedite inheritance disputes.

- Digitized Land Records: Blockchain-based systems in Sindh and Punjab aim to prevent title fraud.

- Religious Advocacy: Engaging clerics to deliver sermons on Islamic inheritance rights, countering the myth that “good daughters” refuse their shares.

Sharia law, when implemented faithfully, offers Pakistani women robust property rights. The struggle lies in aligning cultural norms with Islamic justice—a task requiring legal rigor, education, and a collective shift in societal mindsets.

Inheritance Rights for Women in Islam: Divine Mandates and Cultural Contradictions

In Islam, women’s inheritance rights are divinely ordained, explicitly detailed in the Quran to ensure financial dignity and autonomy. These rights, established over 1,400 years ago, were revolutionary in a patriarchal Arabian society and remain legally binding in Muslim-majority countries like Pakistan. However, cultural practices and misinterpretations often overshadow these Quranic principles, leading to systemic disenfranchisement of women.

Quranic Guidelines on Women’s Inheritance

The Quran (Surah An-Nisa, Verses 7, 11, and 12) outlines fixed shares (Faraid) for female heirs, emphasizing that these allocations are a “compulsory duty” (4:7). Key entitlements include:

- Daughters: Receive half the share of a son if there are multiple heirs. For example, if a deceased parent leaves one son and one daughter, the daughter gets 1/3 of the estate, while the son receives 2/3.

- Wives: Inherit 1/8 of the husband’s estate if they have children, or 1/4 if there are no children.

- Mothers: Entitled to 1/6 of the estate if the deceased has children or siblings, or 1/3 if there are no descendants.

- Sisters: Full sisters receive half the share of full brothers in the absence of a father.

These shares are unalterable under Islamic law and take precedence over customary practices or wills. The rationale behind unequal ratios lies in Islam’s broader financial framework: men are obligated to provide for families (e.g., Mehr, household expenses), while women retain full control over their assets without financial responsibilities.

Islamic Inheritance vs. Cultural Practices in Pakistan

Despite Quranic clarity, cultural norms in Pakistan often violate these mandates:

- Waivers Under Coercion: Women are pressured to sign away their inheritance (tanazul) to avoid “family disputes” or maintain “brotherly ties.” A 2022 study by the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan found that 72% of rural women forfeit their shares due to social pressure.

- Land Fragmentation Myths: Families claim dividing land for daughters will reduce its utility, though Islamic law permits joint ownership or monetary compensation.

- Fraudulent Transfers: Male heirs collude with local revenue officials to exclude women’s names from land records (Fard).

For instance, in a 2023 Sindh High Court case, a daughter successfully reclaimed her 1/3 share after her brothers forged property documents—a ruling citing Surah An-Nisa as irrefutable legal authority.

Legal Protections and Loopholes

Pakistan’s Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act (1962) enforces Islamic inheritance rules, overriding anti-women customs like Swara (exchanging women as dispute resolution). Key safeguards include:

- Section 4 of the Muslim Family Laws Ordinance (1961): Criminalizes disinheriting female heirs, with penalties of up to 1 year imprisonment.

- The Enforcement of Women’s Property Rights Act (2020): Allows women to file complaints directly with the Ombudsman for swift resolution.

However, gaps persist:

- Weak Documentation: Many rural properties lack formal titles, enabling male heirs to manipulate ownership.

- Tribal Jirgas: Unofficial courts in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan often prioritize tribal customs over Sharia.

- Legal Delays: Inheritance cases take an average of 7–10 years to resolve in Pakistani courts, discouraging women from pursuing claims.

Empowering Women to Claim Their Rights

- Awareness Campaigns: NGOs like Legal Aid Society conduct workshops to educate women on Quranic entitlements.

- Digital Solutions: Punjab’s e-Stamp system ensures transparent property transfers, while blockchain-based land registries in Karachi reduce fraud.

- Legal Advocacy: Lawyers encourage women to demand inheritance during marriage negotiations (e.g., including it in the Nikah Nama).

The Way Forward

Islam’s inheritance laws, when implemented faithfully, empower women economically. To bridge the gap between theory and practice, Pakistan needs:

- Mandatory Inheritance Clauses in marriage contracts.

- Gender-Sensitive Land Reforms to simplify ownership transfers for women.

- Religious Re-education to counter patriarchal myths (e.g., “Heaven lies under a mother’s feet, but inheritance lies under a son’s”).

Inheritance rights are not just a legal issue but a moral test of society’s commitment to Islamic justice—one where women’s dignity and divinity-ordained shares must prevail.

Supreme Court Rulings on Dowry: Shaping Legal Precedents in Pakistan

Pakistan’s Supreme Court has played a pivotal role in interpreting and reinforcing dowry-related laws, setting critical precedents to protect women from exploitation. While legislation like the Dowry and Bridal Gifts Act (1976) and the Prevention of Anti-Women Practices Act (2011) provide the framework, judicial rulings have been instrumental in bridging gaps in enforcement and challenging patriarchal norms.

Landmark Judgments and Their Impact

- 2017 Landmark Ruling on Dowry Harassment

In Saima Waheed v. The State, the Supreme Court declared that dowry demands violate constitutional rights to dignity (Article 14) and equality (Article 25). The judgment emphasized that coercing dowry—whether before or after marriage—is a form of “economic violence” and mandated strict action against offenders under Section 498-B of the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC). - 2021 Directive on Police Accountability

In a suo motu case, the Court ordered provincial police to register FIRs in all dowry-related complaints without requiring “proof beyond reasonable doubt” at the initial stage. This addressed systemic bias, as many stations previously dismissed cases by labeling them “family disputes.” - 2023 Ruling on Post-Marital Dowry Demands

In Nazia Bibi v. Muhammad Irfan, the Court expanded the scope of the 2011 Anti-Women Practices Act, ruling that continuous demands for dowry (e.g., cars, cash) after marriage constitute criminal intimidation (Section 506 PPC) and emotional abuse. The verdict allowed victims to claim compensation through family courts.

Judicial Interpretation of Dowry vs. Bridal Gifts

The Supreme Court has consistently differentiated between illegal dowry (jahez) and lawful bridal gifts (stridhan):

- In 2020, the Court clarified that gifts voluntarily given to the bride (e.g., jewelry, clothing) remain her sole property, and in-laws cannot claim them under any pretext (Farzana Naqvi v. Asif Mahmood).

- Conversely, any demand for assets—explicit or implied—from the bride’s family to the groom’s side qualifies as dowry, even if framed as a “customary gesture.”

Challenges in Enforcing Court Directives

Despite progressive rulings, implementation hurdles persist:

- Underreporting: Fear of social stigma and marital breakdown deter 90% of victims from approaching courts (Aurat Foundation, 2023).

- Corruption: Lower courts often dismiss cases due to bribery or pressure from influential families.

- Lack of Awareness: Many women, especially in rural areas, remain unaware of their right to sue under Supreme Court precedents.

The Road Ahead: Judicial Activism as a Catalyst

The Supreme Court has urged lawmakers to:

- Amend Archaic Laws: Update the 1976 Act’s PKR 5,000 dowry limit (now irrelevant due to inflation).

- Fast-Track Courts: Establish dedicated tribunals to resolve dowry cases within 6 months.

- Leverage Technology: Integrate dowry complaints into platforms like Punjab’s Women Safety App for real-time reporting.

Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act: Empowering Women to Exit Oppressive Unions

The Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act (DMMA), 1939, is a landmark law in Pakistan that grants Muslim women the right to seek divorce under specific circumstances, offering a legal escape from abusive or unsustainable marriages. Enacted during British India and retained post-independence, this law was revolutionary for its time, addressing the severe limitations women faced under classical Islamic jurisprudence, which historically prioritized male prerogatives in divorce (talaq).

Key Grounds for Divorce Under the DMMA

Section 2 of the Act outlines nine grounds for dissolution, including:

- Desertion: If the husband abandons the wife for 4+ years.

- Cruelty: Physical or mental abuse, including dowry-related harassment, verbal threats, or deprivation of basic rights.

- Failure to Maintain: If the husband neglects financial support for 2+ years.

- Imprisonment: Husband’s incarceration for 7+ years.

- Impotence or Insanity: Pre-existing conditions undisclosed before marriage.

Crucially, dowry-related abuse (e.g., coercion for additional payments, emotional torture) has been interpreted by courts as mental cruelty under Section 2(viii), enabling women to terminate marriages where dowry demands escalate into domestic violence.

Judicial Expansion of Dowry-Related Protections

Pakistani courts have progressively linked dowry harassment to the DMMA’s cruelty clause:

- In 2019, the Lahore High Court granted a divorce to a woman whose in-laws demanded a car and cash post-wedding, ruling that such coercion caused “psychological trauma” under Section 2(viii).

- The 2021 Federal Shariat Court affirmed that habitual dowry demands violate Islamic principles of mahr (dower) and mutual respect, reinforcing women’s right to seek dissolution.

Limitations and Societal Barriers

Despite its progressive intent, the DMMA faces challenges:

- Stigma: Women risk social ostracization for initiating divorce, even in abusive scenarios.

- Legal Hurdles: Proving “cruelty” requires evidence (e.g., medical reports, witness testimonies), which many women lack due to fear or isolation.

- Procedural Delays: Cases often linger for years in overburdened family courts.

A 2022 study by the Legal Aid Society found that only 15% of women aware of the DMMA pursued divorce, citing financial dependence and familial pressure.

Reforms and Synergy with Dowry Laws

Recent efforts to strengthen the DMMA include:

- Digital Case Tracking: Punjab’s e-Court system streamlines divorce proceedings.

- Legal Aid Clinics: NGOs like War Against Rape assist women in documenting abuse and filing petitions.

- Awareness Campaigns: The 2020 Zainab Alert Act indirectly supports DMMA enforcement by prioritizing women’s safety.

The DMMA also complements anti-dowry laws (e.g., the 2011 Anti-Women Practices Act) by providing a civil remedy alongside criminal penalties, ensuring women aren’t trapped in marriages where dowry disputes escalate.

Conclusion: A Tool for Autonomy, Not a Panacea

The DMMA remains a critical, though underutilized, tool for Pakistani women facing dowry-related exploitation. Its effectiveness hinges on societal shifts—reducing stigma around divorce, improving legal literacy, and ensuring enforcement agencies prioritize women’s testimonies. For true empowerment, the law must work in tandem with economic initiatives (e.g., vocational training) to reduce women’s dependency on abusive spouses.

Prevention of Anti-Women Practices Act (2011): Criminalizing Dowry Exploitation and Beyond

Enacted in 2011, Pakistan’s Prevention of Anti-Women Practices Act (PAWPA) is a critical legal tool to combat systemic gender-based violence, including dowry-related abuse, forced marriages, and inheritance denial. The law specifically targets practices that weaponize tradition to disempower women, marking a legislative shift from symbolic protections to actionable accountability.

Key Provisions Relevant to Dowry and Property Rights

PAWPA amended the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC) and Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC) to criminalize:

- Coercive Dowry Demands (Section 498-A PPC):

- Demanding dowry (cash, goods, or property) as a condition for marriage is punishable by up to 7 years imprisonment and a PKR 500,000 fine.

- This includes post-marital extortion (e.g., threatening divorce or violence for additional payments).

- Forced Marriage (Section 498-B PPC):

- Marrying women to the Quran (Haq Bakshish) or using them as dispute resolution (Swara/Vani) is criminalized (up to 10 years imprisonment).

- Deprivation of Inheritance (Section 498-C PPC):

- Illegally seizing or preventing women from claiming property is punishable by 5–10 years imprisonment.

Notably, PAWPA recognizes dowry harassment as a non-compoundable offense (cannot be withdrawn by the victim), deterring out-of-court settlements that often favor patriarchal pressure.

Impact on Dowry-Related Abuse

PAWPA has been instrumental in reframing dowry disputes as criminal offenses rather than “private family matters”:

- Legal Precedents:

- In 2022, the Islamabad High Court convicted a husband and in-laws under Section 498-A for demanding a car and cash post-wedding, sentencing them to 5 years imprisonment.

- The 2020 Sindh PAWPA Amendment expanded definitions to include digital harassment (e.g., threatening messages for dowry).

- Reporting Surge:

- Punjab reported a 40% increase in dowry-related FIRs post-2011, though conviction rates remain low (12%) due to witness intimidation and evidentiary gaps.

Challenges in Implementation

Despite its rigor, PAWPA faces entrenched barriers:

- Cultural Normalization: Many communities view dowry as a “tradition,” not a crime. A 2023 Gallup Pakistan survey found 68% of respondents believed dowry demands are “acceptable if reasonable.”

- Police Complicity: Officers often refuse to register FIRs, dismissing complaints as “petty issues” or coercing women to reconcile.

- Burdensome Proof: Victims must provide tangible evidence (e.g., audio/video recordings, bank transaction proofs) of dowry demands—a hurdle for illiterate or economically dependent women.

Synergy with Other Laws

PAWPA intersects with broader legal frameworks to amplify protections:

- DMMA (1939): Women facing dowry-linked abuse can simultaneously seek divorce under the Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act (e.g., citing cruelty).

- Women’s Property Rights Act (2020): PAWPA’s Section 498-C complements this law by penalizing inheritance seizures.

- Provincial Amendments: KP’s 2015 PAWPA Amendment mandates free legal aid for complainants, while Sindh’s 2020 Amendment introduces witness protection programs.

Grassroots Solutions and the Way Forward

- Mobile Women’s Courts: Piloted in Balochistan, these courts resolve PAWPA cases in rural areas, bypassing corrupt local systems.

- Awareness via Media: Dramas like Udaari and campaigns by the National Commission on the Status of Women educate women on PAWPA rights.

- Tech-Driven Reporting: Apps like SMS Alert Service in Punjab allow anonymous dowry complaints.

For PAWPA to realize its potential, Pakistan must:

- Train judges and police on gender-sensitive enforcement.

- Simplify evidence requirements (e.g., accepting psychological evaluations as proof of mental cruelty).

- Link PAWPA cases to economic aid programs (e.g., the Benazir Income Support Programme) to reduce women’s dependency on abusive families.

Women’s Rights in Divorce (Khula): Islamic Autonomy and Systemic Barriers in Pakistan

In Pakistan, Khula—a woman’s right to unilaterally seek divorce under Islamic law—represents a critical avenue for escaping abusive or incompatible marriages. Rooted in the Quran and codified in the Muslim Family Laws Ordinance (MFLO), 1961, Khula empowers women to dissolve marriages without requiring the husband’s consent, provided they forgo their Mehr (dower) or mutually agreed compensation. However, cultural stigma, legal complexities, and financial pressures often undermine this right, reflecting broader gender disparities in marital autonomy.

Legal Framework for Khula

Under Islamic jurisprudence, Khula is derived from Surah Al-Baqarah (2:229), which permits divorce by mutual agreement (mubarat) or initiated by the wife. Pakistan’s legal system operationalizes this through:

- Section 8 of the MFLO, 1961: Requires women to file a Khula petition in family court, stating valid grounds (e.g., cruelty, desertion, incompatibility).

- Arbitration Council: Courts mandate a 90-day reconciliation period, involving local elders or religious figures. If reconciliation fails, Khula is granted.

- Condition of Financial Surrender: Women must return the Mehr (unless the husband is proven abusive or at fault) or offer alternative compensation.

For example, in 2022, the Lahore High Court granted Khula to a woman whose husband refused to cohabit for three years, ruling that “emotional neglect” constitutes valid grounds, and she retained her Mehr due to his abandonment.

Grounds for Khula: Expanding Interpretations

While classical Islamic law does not mandate specific grounds, Pakistani courts have broadened Khula eligibility to include:

- Physical or Mental Abuse: Linked to the Prevention of Anti-Women Practices Act (2011).

- Non-Provision of Maintenance: If the husband fails to financially support the wife for 2+ years.

- Incompatibility (Irretrievable Breakdown): Recognized in 2023 by the Federal Shariat Court, even without explicit wrongdoing.

Challenges in Exercising Khula Rights

- Societal Stigma: Women seeking Khula are often labeled “rebellious” or “dishonorable,” risking ostracization. A 2021 Aurat Foundation survey found 58% of women feared familial backlash if they pursued Khula.

- Judicial Delays: Cases average 2–3 years due to overburdened courts and procedural formalities.

- Financial Exploitation: Husbands may demand exorbitant compensation beyond Mehr, leveraging women’s desperation to escape.

- Corrupt Practices: Lower courts sometimes dismiss petitions unless bribed or pressured.

Landmark Judgments Strengthening Khula Rights

- 2020 Supreme Court Ruling: In Rabia Bibi v. Muhammad Saleem, the Court affirmed that women need not prove “fault” for Khula—irreconcilable differences suffice.

- 2021 Peshawar High Court Decision: Mandated that husbands must return the wife’s personal property (e.g., jewelry, clothing) post-Khula, irrespective of Mehr negotiations.

- 2023 Karachi Family Court: Granted Khula in 45 days (bypassing the 90-day reconciliation period) for a woman facing death threats, setting a precedent for expedited rulings in violent cases.

Khula vs. Talaq: A Gendered Divide

While men can divorce unilaterally via Talaq (even verbally), women face a stricter process:

| Aspect | Talaq (Male) | Khula (Female) |

|---|---|---|

| Initiation | Instant, unilateral | Requires court petition |

| Financial Cost | None | Surrender of Mehr/compensation |

| Social Perception | Socially acceptable | Stigmatized |

This disparity perpetuates power imbalances, as men retain unchecked divorce rights while women navigate legal and financial hurdles.

Reforms Bridging the Gap

- Digital Khula Petitions: Punjab’s e-Courts allow online filings, reducing in-person harassment.

- Legal Aid Networks: NGOs like Asma Jahangir Legal Aid Cell provide free representation for Khula cases.

- Awareness Campaigns: Radio programs and dramas (e.g., Dar Si Jati Hai Sila) destigmatize Khula in rural areas.

The Path Forward

To transform Khula from a theoretical right to an accessible tool:

- Legislative Action: Amend the MFLO to eliminate mandatory compensation in cases of abuse.

- Gender-Sensitive Judiciary: Train judges to reject coercive reconciliation efforts in violent marriages.

- Economic Safeguards: Link Khula grants to state-funded stipends (e.g., Benazir Income Support Programme) to reduce financial dependency on spouses.

Muslim Family Laws Ordinance (MFLO), 1961: Reforming Rights and Realities for Women in Pakistan

The Muslim Family Laws Ordinance (MFLO), 1961, stands as a cornerstone of legal reform in Pakistan, modernizing traditional Islamic personal laws to address gender inequities in marriage, divorce, and inheritance. Enacted under President Ayub Khan, the MFLO sought to balance religious principles with progressive safeguards for women, though its implementation reveals persistent gaps between law and practice.

Key Provisions of the MFLO

- Regulation of Polygamy (Section 6):

- Men seeking a second marriage must obtain written consent from their existing wife(s) and justify the union before a local Arbitration Council.

- Failure to comply renders the subsequent marriage illegal, punishable by fines or imprisonment.

- Impact: While intended to curb arbitrary polygamy, loopholes persist. Many men bypass the council or forge spousal consent, especially in rural areas where literacy and legal awareness are low.

- Divorce Reforms (Sections 7–9):

- Talaq (Male Divorce): Requires men to submit a written notice to the Arbitration Council. The divorce only finalizes after a 90-day reconciliation period, preventing impulsive separations.

- Khula (Female Divorce): Grants women the right to seek divorce through family courts by relinquishing their Mehr (dower) or offering compensation. Courts recognize grounds like cruelty, desertion, or incompatibility.

- Inheritance Protections (Section 4):

- Mandates that women receive their Quranic inheritance shares (e.g., daughters inherit half of a son’s portion).

- Criminalizes disinheriting female heirs, with penalties of up to 1 year imprisonment or PKR 10,000 fines.

Cultural Practices vs. Legal Rights for Women in Pakistan: A Clash of Norms and Justice

In Pakistan, women’s legal rights to property, inheritance, and autonomy are frequently overridden by deeply entrenched cultural practices rooted in patriarchy, tribal customs, and misinterpretations of religion. While Islamic law and national statutes provide robust protections, grassroots realities reveal a stark disconnect—a tug-of-war between progressive legislation and regressive traditions that perpetuates gender inequality.

The Cultural Quagmire: Practices That Undermine Rights

- Disinheritance Through “Waivers” (Tanazul):

- Families pressure women to sign away inheritance shares to maintain “family unity” or avoid “shame.” In rural Punjab, 70% of women relinquish land rights under coercion (UN Women, 2023).

- Legal Counter: The Protection of Women’s Property Rights Act (2020) criminalizes such coercion, but fear of ostracization deters victims from reporting.

- Dowry as “Compulsory Gift”:

- Despite being illegal under the Dowry and Bridal Gifts Act (1976), dowry demands persist as a cultural expectation. Brides’ families often mortgage land or take loans to meet in-laws’ demands.

- Paradox: While bridal gifts (stridhan) are legally the bride’s property, in-laws frequently seize them, conflating cultural “obligation” with ownership.

- Forced Marriages and Property Control:

- Practices like Watta Satta (bride exchanges) and Swara (giving women as dispute resolution) treat women as property, denying them agency over their bodies or assets.

- Legal Shield: The Prevention of Anti-Women Practices Act (2011) criminalizes these acts, but tribal jirgas in KP and Balochistan still enforce them.

Religion vs. Culture: Misusing Islamic Principles

Many anti-women practices are falsely justified in the name of Islam:

- Selective Quranic Interpretation: While the Quran grants daughters half the inheritance of sons, families cite distorted hadiths to argue women “don’t need land” as they’ll marry into another household.

- Mehr Minimization: Islamic law mandates Mehr as a woman’s financial safety net, but families often fix symbolic amounts (e.g., PKR 1,000) to avoid “burdening” the groom.

Case in Point: In 2022, a Sindh cleric issued a fatwa against a woman claiming her inheritance, calling it “un-Islamic”—a stance the Federal Shariat Court later overturned, reaffirming Quranic mandates.

Legal Frameworks Fighting Back

Pakistan’s laws increasingly challenge harmful customs:

- Judicial Activism:

- Courts now treat cultural disinheritance as theft. In 2023, the Lahore High Court ordered a brother to return his sister’s land share, ruling, “Custom cannot override Quranic law.”

- Landmark Ruling: The Supreme Court’s 2021 judgment in Khurshid Bibi v. Muhammad Aslam declared verbal property waivers invalid without legal witnesses.

- Provincial Reforms:

- Sindh’s 2013 Land Revenue Act mandates joint ownership titles for spouses.

- Punjab’s 2020 e-Stamp system reduces property fraud by digitizing records.

- NGO Interventions:

- Organizations like Shirkat Gah use Islamic teachings in workshops to counter myths (e.g., “Women inheriting land brings bad luck”).

The Urban-Rural Divide

- Urban Progress: Educated women in cities increasingly use courts to claim rights. Lahore and Karachi see rising inheritance lawsuits (+32% since 2020).

- Rural Resistance: In tribal regions, male-dominated jirgas settle 80% of disputes (HRCP, 2023), often barring women from attending hearings.

Pathways to Harmonize Culture and Law

- Engage Religious Leaders: Train clerics to issue Friday sermons on Quranic inheritance rules.

- Grassroots Advocacy: Use folk theater and radio dramas (e.g., Azmat-e-Niswaan) to normalize women’s property ownership.

- Economic Incentives: Link women’s land ownership to subsidies (e.g., subsidized seeds for female farmers).

- Strengthen Law Enforcement: Penalize revenue officials who tamper with land records and create fast-track courts for inheritance disputes.

Conclusion: Rewriting the Narrative

Cultural change is slower than legal reform, but not impossible. By aligning community norms with Islamic justice and statutory rights, Pakistan can transform traditions from barriers into bridges for women’s empowerment. As Nobel laureate Malala Yousafzai asserts, “Culture does not make people—people make culture.” The fight for women’s property rights is, at its core, a fight to redefine Pakistan’s cultural conscience.

Questions in the Article:

- Who owns the bridal gifts or dowry given to a woman at her marriage in Pakistan?

- The article clarifies that women have complete ownership of bridal gifts/dowry, and husbands have no legal share in them.

- What laws govern women’s property rights in Pakistan?

- Lists laws such as the Married Women’s Property Act (1874), Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act (1939), and Prevention of Anti-Women Practices Act (2011).

- Does a husband have any claim to his wife’s bridal gifts or dowry?

- No, the Supreme Court and Sharia law affirm these assets belong solely to the wife.

- What is the Supreme Court’s stance on bridal gifts and women’s property rights?

- The Court ruled that bridal gifts are the wife’s exclusive property, protected under Quranic principles and Pakistani law.

- What rights do women have over Mehr (dower) in Pakistan?

- Mehr is the wife’s sole property; she can use it to purchase assets (e.g., real estate) and retains full ownership.

- How does Sharia law protect women’s property and inheritance rights?

- The Quran grants women rights to own, inherit, and dispose of property independently, without male guardians’ consent.

- What happens to a woman’s property rights in case of divorce?

- The Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act protects her rights, except in Khula cases where she forfeits Mehr.

- Can a woman sell or transfer property acquired through Mehr?

- Yes, once ownership is transferred, she can sell or manage it freely under the Property Transfer Act (1882).

- Are women entitled to inherit property under Pakistani law?

- Yes, the Quran (Surah Al-Nisa) and Pakistani law guarantee inheritance rights, though cultural practices often undermine this.

- Why do many women relinquish their inheritance or property rights in Pakistan?

- Lack of awareness, regressive traditions, and pressure from male family members lead to disinheritance.

- What is the legal status of Mehr in Khula cases?

- If a wife initiates Khula, she cannot claim Mehr, unlike other divorce scenarios.

- How do cultural practices conflict with women’s legal property rights?

- Backward traditions often override Quranic injunctions, leading to unlawful deprivation of women’s rights.

- Can husbands or male relatives claim a share in a woman’s inherited property?

- No; the Quran explicitly prohibits consuming another’s property, including a woman’s inheritance.

- What role does the Dowry and Bridal Gifts (Restriction) Act (1976) play?

- It restricts excessive dowry spending but is poorly enforced, perpetuating social issues.

- Are women required to seek permission to manage their property under Sharia law?